Why Grozny Can’t Happen Twice

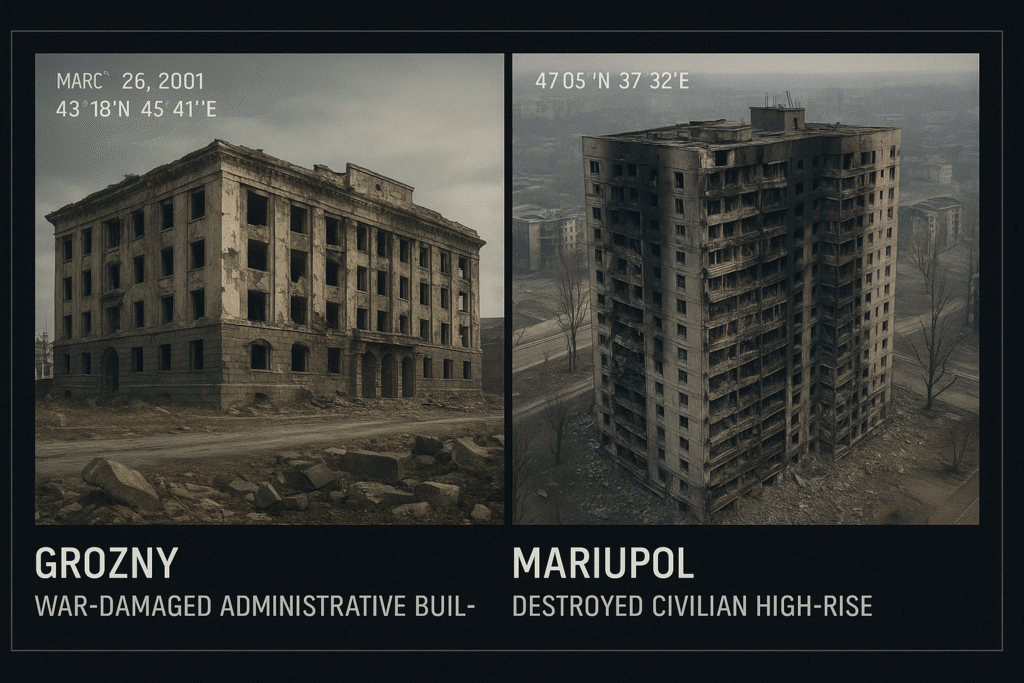

The difference between Grozny and Mariupol is not moral. It is structural. Why Russia can’t ‘Grozny’ Ukraine is not a question of will, but of constraint. Although the Russian Federation still targets civilian infrastructure and levels cities, today’s global warfighting conditions impose boundaries that did not exist in the Chechen theatre. What succeeded in Grozny in 1999 cannot be repeated in Kyiv in 2024 without catastrophic consequences for the Kremlin.

1. From Domestic Annihilation to Global Theatre

During the Second Chechen War, the Russian state applied overwhelming force with minimal external oversight. The near-total destruction of Grozny signalled not only military intent but also a psychological message: resistance would trigger eradication. At that time, Russia operated inside its own borders, under its own narrative, and without any meaningful international cost.

Ukraine presents a categorically different environment. The Kremlin faces a sovereign opponent, international surveillance, and geopolitical stakes far beyond Chechnya’s local rebellion. Consequently, although the destruction remains severe, it is far more calibrated.

Russia’s violence today reflects constraint—not mercy.

2. War Under Observation: Visibility as a Deterrent

In Grozny, Russian forces acted without fear of international exposure. Western media maintained a minimal presence, satellite surveillance was primitive, and digital evidence scarcely circulated. This allowed Moscow to bomb entire districts without diplomatic or military repercussions.

In Ukraine, every artillery strike can be geolocated, timestamped, and globally disseminated within minutes. Footage from Bakhmut or Mariupol circulates in real time. Western intelligence agencies monitor Russian troop movements using open-source and classified imagery, while OSINT researchers reconstruct war crimes within hours.

Because of this visibility, Russia cannot conduct large-scale annihilation without provoking escalatory responses, such as increased NATO aid or legal consequences.

“Visibility has become a strategic variable.” — RAND, 2025 [1]

3. Legitimacy and Legal Architecture

The Chechen Wars unfolded under the legal framework of Russian internal affairs. The Kremlin branded Chechen resistance as terrorism, which justified full-spectrum repression. Western actors, although concerned, lacked the standing or leverage to intervene decisively.

By contrast, Ukraine is a recognised sovereign state. Its government operates under international law and receives explicit support from NATO members. Russia must therefore manage its violence within a rhetorical framework that preserves plausible deniability.

This explains the Kremlin’s terminology: “special military operation,” “de-Nazification,” and “liberation.” The war’s legitimacy depends on avoiding language and actions that could trigger a broader legal or military backlash.

4. Narrative Contradictions: Kinship as Constraint

The Russian regime has spent decades portraying Ukraine not as foreign, but as fraternal. Putin himself refers to Ukrainians as part of a “shared spiritual space” with Russia. Because of this narrative, the Kremlin cannot annihilate Ukrainian identity without undermining its own ideological foundation.

During the Chechen campaign, such internal contradictions did not exist. The Russian public viewed Chechnya through the lens of counterinsurgency and ethnic difference. The result was a blank cheque for state violence.

Today, however, the Kremlin must reconcile its ideological fiction of brotherhood with battlefield realities. Mass destruction erodes that narrative, weakening both domestic support and external justification.

Propaganda requires internal consistency. Genocide does not.

5. Logistics and Operational Reach

In Chechnya, Russian forces operated with short supply chains and direct control over territory. Although resistance was fierce, logistical dominance made total destruction feasible. Urban operations followed Soviet patterns: encircle, flatten, occupy.

Ukraine imposes far greater logistical burdens. Russia must supply multiple fronts, defend elongated rail corridors, and operate beyond its own borders. Western intelligence monitors these supply routes, targeting them with precision artillery and sabotage campaigns.

Furthermore, Ukraine’s modern armed forces do not allow easy encirclement. Each city requires months of siege and continuous resource expenditure. Because of these factors, Russia cannot replicate Grozny-scale destruction at will.

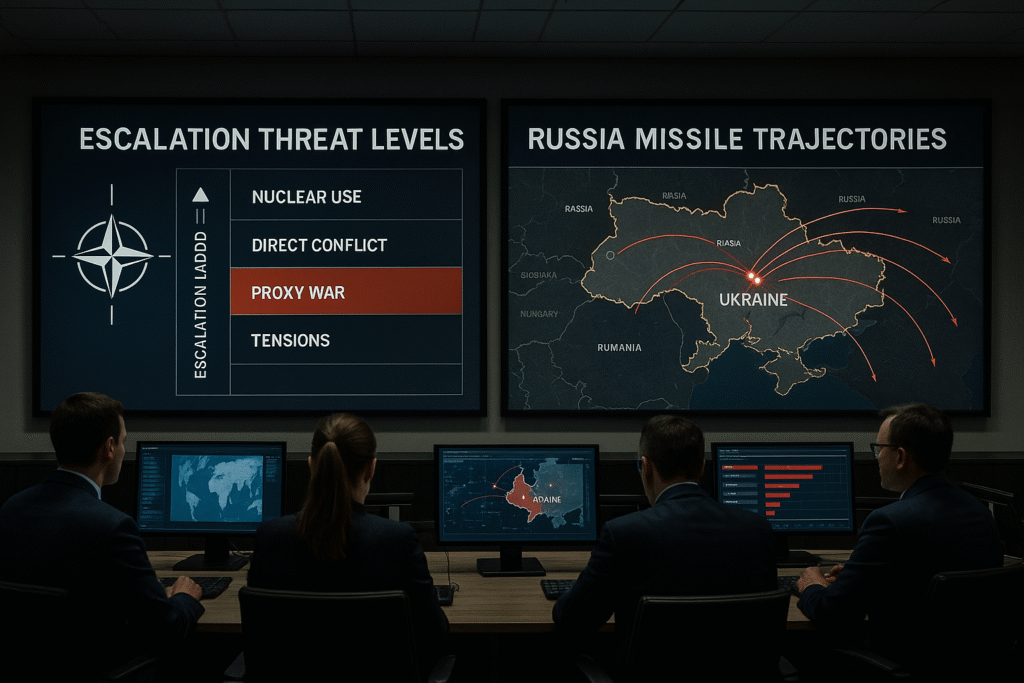

6. Escalation Risk and Strategic Limits

Perhaps the most critical difference lies in the calculus of escalation. Chechnya posed no risk of international confrontation. Even at the height of its brutality, the Russian campaign faced only rhetorical condemnation.

Ukraine, however, borders NATO. Escalating violence—even through conventional means—carries significant risk. A single miscalculated strike could provoke horizontal escalation, such as direct Western military involvement. Alternatively, it could force Russia into vertical escalation, including tactical nuclear use.

Thus, the Kremlin must balance brutality with restraint. Hybrid war doctrine hinges on calibrated disruption: enough violence to degrade the opponent, but not enough to trigger Western consensus for direct confrontation.

In this theatre, overreach equals collapse.

7. Brutality With Boundaries

The Kremlin has not reformed its methods. It remains willing to destroy cities and civilian infrastructure. However, it cannot pursue unrestricted destruction in Ukraine without shattering the geopolitical equilibrium on which it depends.

Structural forces—not humanitarian concerns—now shape the limits of Russian warfare. These include real-time visibility, legal status, narrative fragility, logistical complexity, and escalation risk.

Although Ukraine endures relentless attack, it avoids the fate of Grozny not because Moscow holds back, but because the system now holds it in check.

Join the Civilian Intelligence Mission

Frontline Europa exists to decode the deeper structures shaping modern conflict. If you value intelligence-grade journalism, strategic analysis, and forensic war reporting, please consider supporting our mission.

References

- Treyger, E., Cheravitch, L., & Cohen, R. (2022). Russian Disinformation Efforts on Social Media. RAND Corporation.

- Baudrillard, J. (1995). The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Indiana University Press.

- Mazarr, M. J., et al. (2025). Thinking Through Protracted War with China: Nine Scenarios. RAND Corporation.