The Man Who Survived History

“The last man had no desire to be recognized as greater than others, and without such desire no excellence or achievement was possible.”

— Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (1992)

When Francis Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man, announcing The Exhausted Victory of European politics, he did not claim that events would cease. He claimed that the motor of ideological evolution had failed. The twentieth century, he argued, had settled the central dispute of political modernity. Liberal democracy — despite its flaws, fragilities, and internal contradictions — had emerged as the only system that combined material prosperity with reciprocal recognition.

But with this victory came something else: a civilisational torpor. The loss was not of power, but of purpose. The book is not a triumphalist account of Western ascendancy; it is a strategic diagnosis of its spiritual and ideological exhaustion. For the modern European condition — one of hollow institutions, declining public courage, and hybrid war without ideological immunity — Fukuyama’s thesis is structurally essential.

1. History as Ideological Evolution

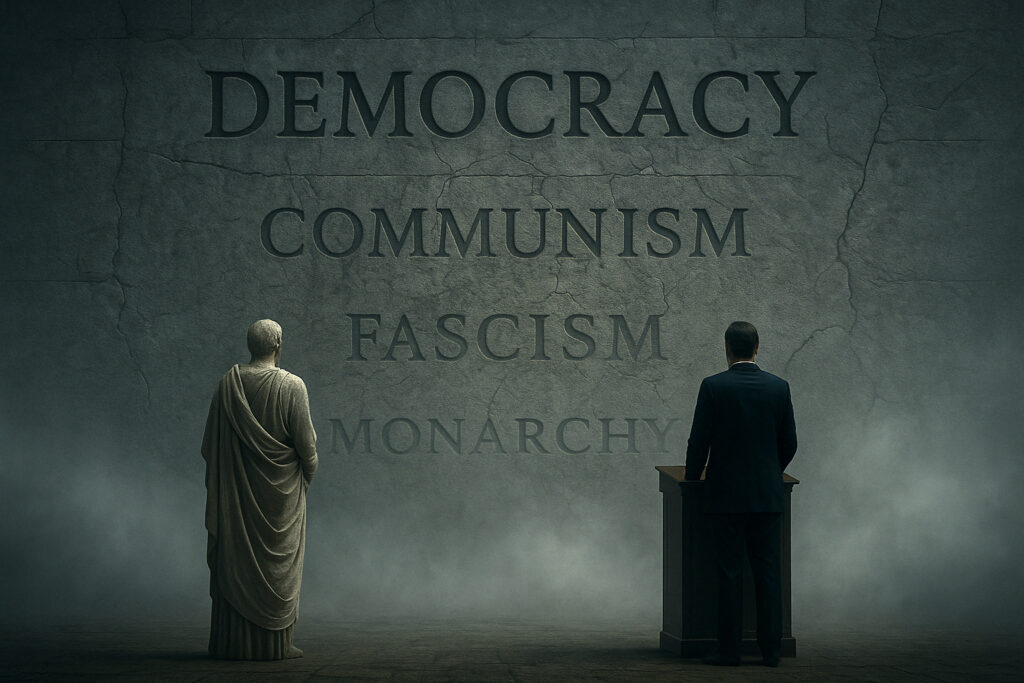

Fukuyama defines history not as chronology but as a directional process. Drawing on G.W.F. Hegel’s dialectic and Kojevian interpretation, he argues that human history is intelligible only when understood as a progressive struggle for political recognition. This struggle, driven by thymos — the human need to be acknowledged as possessing dignity — has generated the succession of regimes throughout history: from tribalism, monarchy, aristocracy, and theocracy to fascism, communism, and finally, liberal democracy.

The concept of thymos is central. It names the part of the soul that experiences pride, anger, shame, and the drive to assert worth. As Fukuyama writes:

“The desire for recognition, and the accompanying emotions of anger, shame, and pride, are parts of the human personality critical to political life. According to Hegel, they are what drives the whole historical process.” [1]

This is not a materialist thesis. It is a philosophical anthropology. While Marxist models explain human conflict through class, and liberal models through utility, Fukuyama insists that dignity is prior to both. Men will die not just for food or comfort, but to be seen. The result is history as a struggle to embed recognition in political structures.

2. The Terminal Form of Governance

According to Fukuyama, liberal democracy is not the best regime because it is perfect. It is the best regime because it contains no internal contradiction that compels its transcendence. Communism collapsed under its own untruths. Fascism discredited itself through war and genocide. Monarchy and theocracy cannot justify hereditary or divine rule in a rational, secular age. Liberal democracy alone satisfies both of man’s demands: economic desire and thymotic recognition.

The implication is radical. Liberal democracy is not a phase. It is the final form of governance. Fukuyama calls this the “universal and homogeneous state,” borrowing from Kojeve:

“What man had been seeking throughout the course of history … was recognition. In the modern world, he finally found it, and was ‘completely satisfied.’” [1]

Yet this finality comes at a price. If there are no new ideologies, no new revolutions, no new ideals, then the end of history does not mean peace. It means stagnation. The human spirit, deprived of higher causes, drifts into triviality. Fukuyama does not conceal this danger. He calls the creature who emerges the Last Man.

3. The Last Man and Strategic Decay

The Last Man is not tyrannical. He is pacified. He demands rights, comfort, and recognition, but nothing higher. His thymos is flatlined. He avoids war not from moral strength but from existential fatigue. This figure, adapted from Nietzsche’s critique of modernity, represents the atrophy of civilisational vigour at the very moment of its institutional success.

In the European context, this figure is visible not just culturally but strategically. The Last Man is the official who manages decline, the bureaucrat who mistakes technocracy for legitimacy, the journalist who refuses conflict because he refuses to believe in anything. Hybrid war flourishes in this terrain because liberal democracies are materially durable but narratively hollow.

Fukuyama’s warning is exact:

“The typical citizen of a liberal democracy was a ‘last man’ who, schooled by the founders of modern liberalism, gave up prideful belief in his or her own superior worth in favour of comfortable self-preservation.” [1]

The strategic liability is not a failure of defence, but a collapse of conviction. A society may protect its infrastructure yet still falter when it can no longer articulate what it exists to defend.

4. Recognition as the Engine of Conflict

The thymotic structure of man ensures that peace cannot be reduced to material calculation. The desire to be recognised as superior still simmers beneath the surface. Fukuyama identifies nationalism, religious extremism, and ideological radicalism as return forms of thymos. These are not deviations. They are predictable consequences of liberal democracy’s failure to fully satisfy recognition.

This is why hybrid war takes the form it does: psychological operations, identity sabotage, symbolic subversion. Opponents of the liberal order do not need to defeat its armies. They only need to demonstrate that it lacks meaning. In this way, thymos becomes the battlefield, and liberalism’s own refusal to engage in moral combat becomes its core weakness.

The question Fukuyama leaves us with is not whether liberal democracy is institutionally durable. It is whether it can produce citizens who believe in it.

5. Strategic Implications for Europe

The End of History and the Last Man is not a work of prediction. It is a work of strategic philosophy. Its warning is not about tyranny from without, but entropy from within. Fukuyama saw that when recognition is no longer linked to sacrifice, conviction, or excellence, it collapses into proceduralism. And procedural states do not survive strategic pressure.

For Europe, this is no longer theoretical. The Last Man governs Brussels. He signs decrees, funds bureaucracies, and reacts to crises without metaphysical commitment. He cannot resist ideological aggression because he does not believe in ideological defence. Fukuyama’s book is essential not because it explains the end of history, but because it maps the battlefield after it.

Read the Autopsy of Ideology

Those serious about understanding the structural causes of institutional decay, ideological exhaustion, and post-liberal vulnerability must read The End of History and the Last Man in full. This is not a book of policy. It is a book of metaphysical realism. It answers the question no official doctrine wants to face: what happens when the regime wins, but the man dies inside it?

Buy The End of History and the Last Man via our affiliate link to support further strategic briefings.

Support Frontline Europa on Patreon to fund more field intelligence, philosophical analysis, and institutional-grade reporting: patreon.com/frontlineeuropa

References

- Fukuyama, F. (1992). The End of History and the Last Man. New York: The Free Press.

- Kojeve, A. (1947). Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. New York: Basic Books.

- Hegel, G.W.F. (1807). Phenomenology of Spirit. Trans. A.V. Miller. Oxford University Press.

- Nietzsche, F. (1887). On the Genealogy of Morality. Trans. C. Diethe. Cambridge University Press.