When Strength Became a Crime

What if the West’s ruling ideology wasn’t liberalism or capitalism, but something far more entropic: a totalising cult of weakening? What if the most powerful taboo in modern political life wasn’t racism or extremism, but metaphysical conviction itself? R.R. Reno’s Return of the Strong Gods names this condition for what it is: a civilizational consensus built not to flourish, but to forget.

1. Context for Collapse

In the decades since the Second World War, a paradox has come to define Western governance: the louder its institutions speak of progress, inclusion, and openness, the more atomised and spiritually disoriented its populations become. R.R. Reno’s Return of the Strong Gods offers not a cultural lament, but a structural diagnosis. He argues that the postwar order was founded on a metaphysical prohibition—a deliberate project to disarm public life of its capacity for truth, loyalty, and transcendence. This project, initially framed as a necessary safeguard against fascism and ideological tyranny, has become a self-perpetuating doctrine that now inhibits the West’s capacity to remember what it is.

This article examines Reno’s book as a strategic artefact: not simply a critique of modern liberalism, but a forensic map of how the West was reconstructed around a set of anti-metaphysical imperatives. From Popper’s procedural epistemology to the Frankfurt School’s social psychology, Reno tracks how elite consensus has pathologised cohesion itself. What emerges is not a polemic, but a framework for decoding the invisible prohibitions that govern our political imagination.

2. Postwar Consensus as Anti-Metaphysical Doctrin

Reno situates the post-1945 period not as a return to order, but as an epochal rupture. The horrors of totalitarian violence gave rise to what he calls the “anti-imperatives”: anti-fascism, anti-racism, anti-authoritarianism. These were not temporary precautions. They hardened into a new metaphysical regime—one that treats strength, unity, and loyalty not as goods to be cultivated, but as risks to be contained. The Western project became defined by the pursuit of openness and the policing of belief.

This reorientation was not merely political. It reorganised the deep structure of Western moral and intellectual life. Metaphysical suspicion became a virtue. Institutional authority, religious conviction, and national identity—each became suspect. The strong gods, those enduring sources of shared love and civilizational cohesion, were systematically driven from public life.

3. Philosophical Infrastructure of Weakening

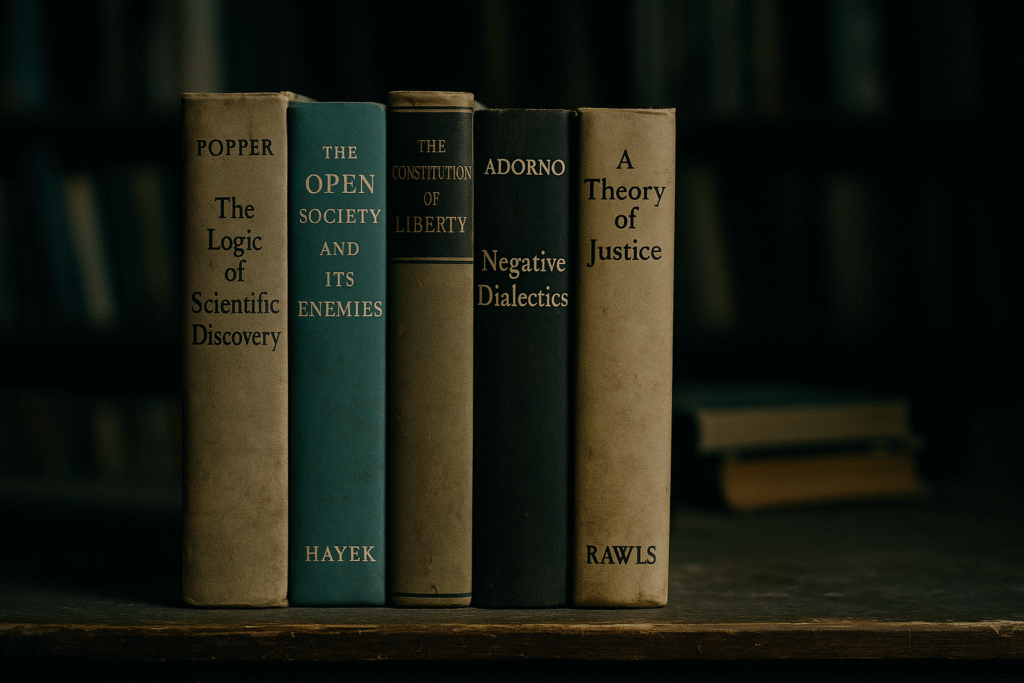

Reno traces the conversion of postwar fear into philosophical orthodoxy. Karl Popper’s Open Society and Its Enemies framed metaphysical conviction as proto-fascist [1]. Hayek’s Road to Serfdom pathologised collective purpose as the seedbed of tyranny [2]. The Frankfurt School medicalised traditional belief structures, most notably in The Authoritarian Personality, which classified conventional morality as a latent form of bigotry [3].

These texts were not fringe interventions. They became doctrinal. The liberal centre-left took up moral deregulation, while the centre-right absorbed economic deregulation. Both accepted metaphysical disarmament as the price of peace. A bipartisan consensus emerged that rejected any vision of the common good rooted in shared truth. Reno calls this the postwar consensus, but it might be described as an architecture of civilisational amnesia.

4. The Pathologisation of Solidarity

Perhaps Reno’s most strategic insight is his framing of political correctness and diversity orthodoxy as enforcement mechanisms, not for equality, but for metaphysical restraint. These are not incidental cultural shifts. They are rituals of governance for a society that no longer permits transcendence. The strongest taboo in the postwar West is not immorality, but unity. To speak of “we” is to risk being classified as dangerous.

Reno documents how elite institutions increasingly treat any invocation of truth, nationhood, or loyalty as authoritarian regression. Populist movements, which often function as unconscious protests against metaphysical vacuity, are not engaged but exorcised. Their demands for meaning are reclassified as threats. This is the logic of negative piety: a society that atones not for its sins, but for its former strength.

5. Reconstructing the Conditions for Truth

Reno does not call for a return to pre-war ideologies. His critique is not nostalgic but architectural. The strong gods are not mere symbols of past orders but structural necessities for any society that wishes to act coherently in history. A civilisation that refuses to name its sacred cannot sustain itself. Having outlawed its own sources of cohesion, the West now finds itself defenceless against both internal dissolution and external pressure.

The recovery of metaphysical depth is not a cultural luxury but a geopolitical necessity. Reno suggests that the only viable path forward is to rehabilitate the very instincts that the postwar order sought to suppress: the willingness to name what matters, to bind the public to shared truths, and to recover the sacred vocabulary of love, sacrifice, and solidarity.

6. Reclaiming the Civilisational Voice

Return of the Strong Gods is not a policy book. It is a civilisational audit. Reno exposes the metaphysical assumptions that underpin the Western consensus and shows how its rituals of openness now function as instruments of paralysis. For those seeking to understand why the West cannot cohere, cannot act, and cannot defend itself, this is not just a book worth reading—it is a strategic document.

Read, Recover, Reconstruct

To explore the full depth of R.R. Reno’s argument, we encourage readers to purchase Return of the Strong Gods via our affiliate link. Every purchase supports our strategic research.

To sustain this kind of forensic journalism and civilisational analysis, please support Frontline Europa on Patreon.

REFERENCES

1. Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Routledge, 1945.

2. Hayek, Friedrich. The Road to Serfdom. University of Chicago Press, 1944.

3. Adorno, T.W., et al. The Authoritarian Personality. Harper, 1950.

4. Reno, R.R. Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West. Regnery Gateway, 2019.

5. Rawls, John. Political Liberalism. Columbia University Press, 1993.