The War You Can’t See

The East StratCom Task Force was not created to fight with weapons, but with words. Formed in 2015 after Russia annexed Crimea, this small EU unit was tasked with a deceptively large mission: defend Europe from hostile disinformation. At the time, few understood how deeply narrative warfare had already become embedded in European society — or how unprepared the West was to confront it.

This wasn’t conventional propaganda. It was fast, fragmented, and viral, spreading through memes, Telegram threads, influencer posts, and shadow networks. Its aim was not persuasion but confusion; not victory but paralysis. And while Moscow treated information as a battlefield, Brussels treated it as a technical challenge.

Nearly a decade later, StratCom remains a watchtower — alert but powerless. It tracks the flow of weaponised narratives, but it doesn’t disrupt them. It issues reports, but it doesn’t shape the fight. The EU recognised the war, but built a monitoring team instead of a defence force. As a result, Europe’s cognitive frontline remains exposed.

I. A Bureaucratic Baby Born of Geopolitical Shock

European leaders launched the East StratCom Task Force after Russia seized Crimea in 2014. At the time, Russian state media and social platforms flooded Europe with narratives justifying the invasion and delegitimising Ukraine, NATO, and the EU.

In March 2015, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs received a directive from the European Council to mount a communication strategy. In response, the European External Action Service (EEAS) established its Strategic Communications (StratCom) unit.

However, internal EU disputes — with Eastern countries demanding urgency and Western states fearing the optics of propaganda — led to a weak compromise. Officials embedded the Task Force within the EEAS, denied it legal authority, and provided it with minimal funding.

Originally, StratCom had three goals:

- Communicate EU policies in Eastern Partnership countries

- Support independent journalism

- Identify and counter foreign disinformation

Despite this broad scope, the Task Force primarily focuses on monitoring Kremlin-linked narratives.

II. EUvsDisinfo: An Archive of Propaganda Without Teeth

StratCom’s most public initiative is EUvsDisinfo, which launched in November 2015. The platform now houses over 15,600 documented cases of Kremlin-linked disinformation.

These entries go beyond fact-checking. Analysts map recurring storylines across languages and platforms — from RT broadcasts to Telegram memes — exposing consistent themes such as: “Ukraine is Nazi,” “NATO is the aggressor,” or “the EU is collapsing.”

In 2019, GeenStijl, a Dutch news outlet, successfully sued to have its name removed from the database. The court found that StratCom lacked a legal basis for blacklisting EU-based publications, revealing a structural weakness.

Despite its analytical depth, EUvsDisinfo rarely reaches the platforms where these narratives dominate. It does not counter content on TikTok, YouTube, or encrypted networks like Telegram. Therefore, it monitors threats but does little to mitigate them.

III. Understaffed, Outgunned, and Politically Cornered

As of 2023, fewer than 20 people worked at StratCom. Their annual budget stayed under €2 million, according to the EU’s Financial Transparency System. Meanwhile, Russia, China, and Iran scale coordinated information offensives.

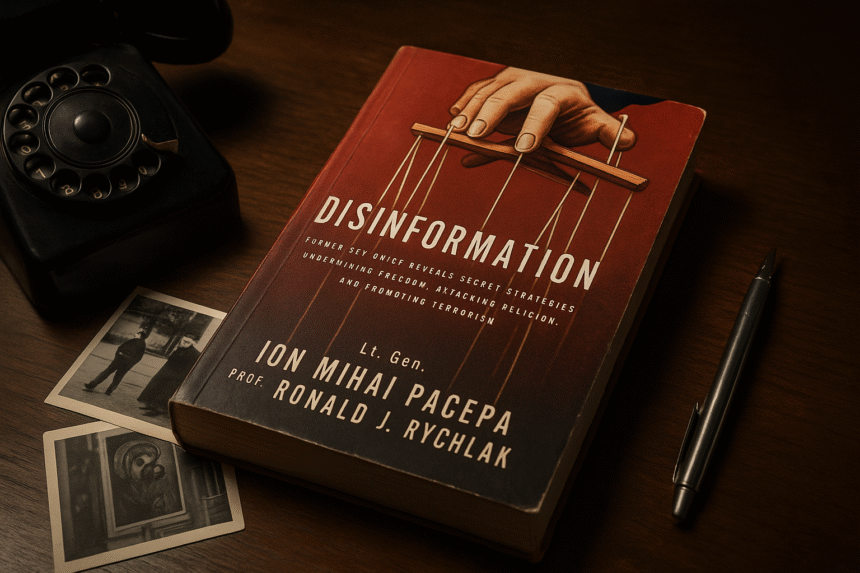

For example, Russia’s GRU Unit 54777 manages psychological operations through proxy media and NGOs. China’s United Front Work Department uses diaspora influencers and front groups. Iran distributes disinformation via multilingual networks like Press TV and Tasnim.

StratCom’s analysts, though experienced and multilingual, operate without legal enforcement tools or real-time tech integration. They track threats, write briefings, and submit reports — but lack the authority to take action.

IV. The Front Expands: Slovakia, France, Telegram, and the Collapse of Boundaries

Disinformation no longer affects only Ukraine or the eastern fringe. In fact, its reach now shapes elections and narratives within EU borders:

- In Slovakia (2023), Kremlin-aligned Telegram channels flooded users with anti-NATO rhetoric and conspiracies. These narratives helped swing the parliamentary election toward a pro-Russian coalition.

- During the France protests (2023–24), Russian and Iranian-linked Telegram networks circulated fabricated police brutality videos. Analysts traced the content back to foreign IP clusters.

- In Germany, COVID-era protest networks like Querdenker merged with pro-Kremlin narratives. These now appear regularly across German-language TikTok and YouTube.

StratCom identifies these threats in real time. However, it lacks the authority to intervene. It cannot remove content, launch counter-campaigns, or coordinate EU-wide mitigation. As a result, it must watch the same campaigns it was created to confront.

V. Structure Without Doctrine: How the EU Fights Without Belief

Unlike its adversaries, the EU lacks a doctrine of information warfare. Russia employs the Gerasimov Doctrine, integrating non-military operations into a broader geopolitical strategy. China’s “Three Warfares” doctrine formalises psychological, media, and legal warfare.

In contrast, the EU treats disinformation as a regulatory issue. Consequently, StratCom performs like a research unit, while adversaries wage real-time cognitive war. Its analysts produce knowledge but not defence. They brief policymakers but cannot engage the public.

“Russia has a strategy. The EU has guidelines.”

A Task Force That Warns, But Cannot Shield

The East StratCom Task Force was never designed to wage war. Its purpose was to signal Europe’s awareness. But in an era of psychological warfare, signals without action vanish into the noise.

StratCom has succeeded in what it was tasked to do — observe, monitor, and report. However, its structure limits its effectiveness. Until the EU builds a doctrine that matches the scale of the threat, the Task Force will remain a silent witness to a war fought in plain sight.

What Europe needs now is not more monitoring. It needs mobilisation.