Sovereignty Without Minds

In 2025, digital sovereignty defines the state of Europe’s cognitive occupation. European leaders speak often of sovereignty. They invoke it in the context of energy, borders, law, and defence. Yet they seldom talk of the sovereignty of thought. Europe’s cognitive space—what its people see, know, trust, and believe—is not European. Instead, it is algorithmically managed, commercially exploited, and strategically shaped by entities located far outside the EU’s legal or cultural domain.

This condition is not new. It did not arrive with the Ukraine war or the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, it is the long-term product of a civilisational transfer of influence: a quiet but total shift in who owns the pipes, the platforms, the feeds, and the informational habits of European publics. Europe was not invaded. Instead, it experienced cognitive occupation—voluntarily, profitably, and almost silently. Today, this cognitive occupation underpins the structural power imbalance between Europe and the platforms on which it depends.

1. Infrastructure Dependency Was the Entry Point

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) of 2024 identifies six gatekeepers of Europe’s digital landscape: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and ByteDance. Five of these are American. Notably, none operate under Europe’s democratic or judicial control. According to the DMA Annual Report 2024, these entities govern everything from search infrastructure to advertising algorithms and data collection ecosystems.

Although the DMA outlines rights and restrictions, the Commission concedes that enforcement remains “under development.” Crucially, it offers no real provision for replacing or bypassing these foreign-owned systems. As a result, cloud computing, marketplace architecture, and user analytics remain centralised in Seattle, Silicon Valley, or Shenzhen. In this environment, Europe chooses to consume, regulate, and hope.

Ion Mihai Pacepa warned in Disinformation:

“The most successful influence operations are those that convince the target society it remains in control.”¹

That illusion now defines Europe’s digital relationship with the United States. Moreover, this illusion reinforces the mechanics of cognitive occupation.

2. Platform Logic Becomes Political Logic

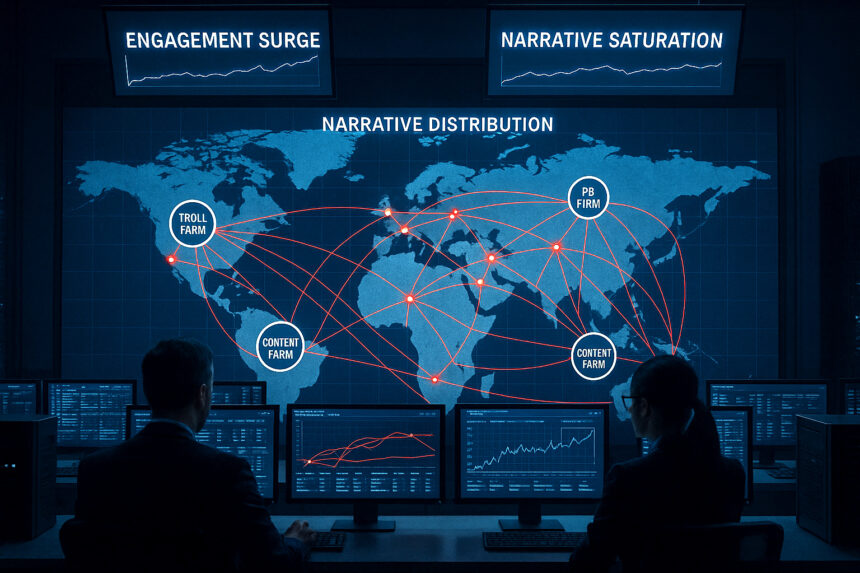

Control of platforms is not neutral. Instead, it defines the cognitive terrain. The feeds people scroll through, the news they see, the voices they hear and ignore—algorithms shape all. Most of them remain proprietary, experimental, and engineered for monetisation and retention, not truth.

Renée DiResta, in Invisible Rulers, explains how narrative dominance now functions:

“Information flows are no longer public utilities. They are asset classes—curated by design, optimised for effect, and invisibly orchestrated to reflect the interests of those who control the infrastructure.”²

This design logic does not stop at consumer behaviour. Instead, it bleeds into policy perception, public trust, social cohesion, and even national security framing. For example, European discourse about Ukraine, Israel-Palestine, climate, gender, or migration unfolds inside frameworks built in California. The fact that these platforms remain based in the U.S. is not incidental—it is strategic.

The 2024 DMA report confirms this domination. However, it fails to address its strategic implications. It regulates market behaviour but does not address cognitive sovereignty. Therefore, without confronting platform ownership, the EU cannot resist cognitive occupation.

3. India Acted. Europe Did Not.

In 2020, following military clashes with Chinese forces in the Himalayas, India banned TikTok and 58 other Chinese apps on national security grounds. The rationale was simple: information ecosystems, when owned or influenced by adversarial states, become vectors of psychological and societal manipulation.

That action was not rhetorical. It was sovereign.

By contrast, Europe has allowed U.S. platforms to deepen their reach across every layer of public and private digital life. ByteDance still operates. Meta retains full-spectrum dominance of social media advertising. Meanwhile, TikTok’s influence among youth demographics continues to expand.

As Jason Stanley warns in How Propaganda Works:

“Democracies are especially vulnerable when propaganda comes disguised as choice.”³

That disguise now defines the European media environment. Furthermore, that disguise is the operational form of cognitive occupation.

4. Cognitive Sovereignty Was Never Recovered After 2007

The 2007 cyberattacks against Estonia were the world’s first major warning that digital infrastructure could be a target on the battlefield. The RAND report, “Understanding Russia’s Intervention in Syria,” and ENISA’s threat landscapes both highlight how hybrid models—combining military, diplomatic, and narrative instruments—have only matured.

Nevertheless, Europe failed to build a domestic internet architecture. Nor did it develop native algorithmic ecosystems. Furthermore, policymakers did not nationalise or harden cognitive supply chains.

Rather than reverse this trend, they continued to externalise control to convenience.

Even the EU’s most forward-looking institutions, such as the DMA or the Cybersecurity Act, only regulate dependency. They do not replace it.

Russ Kick summarised this blindness sharply in Everything You Know Is Wrong:

“The most effective falsehoods are the ones we live inside. Not the ones we reject.”⁴

Europe is now fully immersed in cognitive occupation, unable to map what it cannot name.

5. Europe’s Minds Are Not Its Own

Cognitive occupation is not dramatic. Instead, it is ambient. It arrives in the form of default settings, trending tabs, auto-complete suggestions, ad targeting, shadow bans, and feed architecture. It is behavioural rather than confrontational. Its power lies in shaping what Europeans do not think to question.

To regain political sovereignty without informational sovereignty is to build law atop illusion. Every article published, every debate aired, and every protest livestreamed depends on infrastructure owned, operated, and mediated by external actors. Consequently, no election, referendum, or public discussion in Europe escapes the logic of foreign platforms.

Europe has national governments. It has courts. It has a parliament. Still, it does not control the way its citizens perceive reality. The EU governs politically while surrendering cognitively.

Conclusion

Europe was not cognitively colonised by accident. Instead, it was colonised through choice, dependence, and neglect. The illusion of autonomy, sustained by regulatory theatre, has delayed any meaningful confrontation with the fact that Europe does not own its cognitive lifelines.

The 2024 DMA report proves this unintentionally. So do the algorithms that prioritise distraction over substance, division over coherence, and virality over truth.

A continent that cannot control its informational metabolism cannot claim to be sovereign. It can only act inside the confines of its programming.

The first battle has already been fought. And it was lost not in parliament, but in the feed. This is the core mechanism of cognitive occupation.

Support This Work

Cognitive occupation is not a metaphor. It is a measurable reality shaping Europe’s future—quietly, deliberately, and structurally. At Frontline Europa, we document what others ignore: the systems, doctrines, and engineered dependencies eroding European sovereignty from within.

Our investigations are independent, unsponsored, and strategically focused. To continue publishing forensic analysis at this level—free from commercial filters and ideological agendas—we need your support.

If you value this work, consider supporting us via Patreon, or contact us directly to contribute to the platform’s long-term mission. Every contribution strengthens the information resistance.

References

- Ion Mihai Pacepa, Disinformation, (Washington, DC: WND Books, 2013).

- Renée DiResta, Invisible Rulers: Who Turn Lies into Reality, (New York: PublicAffairs, 2021).

- Jason Stanley, How Propaganda Works, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Russ Kick, Everything You Know Is Wrong: The Disinformation Guide to Secrets and Lies, (New York: The Disinformation Company, 2002).

- New York Times, “India Bans Nearly 60 Chinese Apps, Including TikTok and WeChat,” June 29, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/29/world/asia/tik-tok-banned-india-china.html

- BBC News, “How a cyber attack transformed Estonia,” April 27, 2017. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/39655415

- RAND Corporation, Countering Russian Influence in the Middle East and North Africa, RR3180, 2020. Available at:https://www.rand.org

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), “Cyber Threat Landscape.” Available at: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/cyber-threats/threat-landscape